It’s a story often told — we live in the Information Age with enormous resources at our fingertips. Students, faculty and millions of others looking for information often rely on the Internet rather than a trip to a building to check out books or ask for help from research specialists called librarians.

In the race to keep up with technology, it’s been suggested that libraries are perhaps outdated notions, but the picture is clouded with other facts: more books than ever before are being published — and read — and libraries with computer labs and extensive digital resources are busier than ever.

Still, for libraries to avoid the prophecies of extinction, serious adaptation is needed. Predicting the future is no small chore but that doesn’t stop the armchair prognosticators. Academic work and the library in particular have been fodder for futurists, especially those seeing upheavals ahead.

Crystal Ball Time

Fairleigh Dickinson University entered the debate last year with an essay competition co-sponsored by University Libraries and the New Jersey Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL). Titled “Visions: The Academic Library in 2012,” the effort looked a decade ahead. An overview of the proposals submitted — by librarians and others, by those inside and outside the University community — was published online in May (http://dlib.org/dlib/may03/marcum/05marcum.html) and has triggered discussions from New Jersey to Thailand.

The prevailing conviction is that technology serves as the driving force determining change in academic libraries. Two of the most striking essays predicted that academic libraries in 2012 will use multiple media extensively. Stuart Silverstone, a Los Angeles media guru (and nonlibrarian) envisions a visual infrastructure of video-displaying walls, situation-room theaters, learning “cafeterias,” and dispersed, theme-centered constructions using multimedia “books” and other knowledge-based packages, exhibits, arcades and laboratories. His “Big Picture Overview” anticipates virtual conferencing with access to extensive media storage.

William Kennedy, FDU’s director of Web operations, sees similar uses of technology, but he describes the situation in terms of metaphors. No longer a room with a host, the library of 2012 will be experienced as a virtual reality with a “zoom atlas” to whisk the learner to other places, with time travel to jump back into history or forward into the future, and with enacted dialogue to allow “conversations” with people from other times and places.

The winning essay, “Cybrarians in InfoSpace,” submitted by a team of library school professors, pictures librarians as technologists, working with tools that utilize artificial intelligence and multitasking to assist learners in creating individualized information portfolios. Communicating through virtual reality helmets and v-mail, and using diagnostic tools to customize resources to individual profiles, cybrarians will provide effective support for problem solving and discovery groups.

Certainties about the future are nearly impossible, however, technology will play a large role in the library of the future. And there are many ways that the library can use technology to advance its mission. But before plunging ahead, some perspective should be placed on our so-called “Age of Information.”

Age of Information or Age of Learning?

To describe today as an Information Age and to give pre-eminence to information is to misread the situation. The amount of information available is tremendous. The assumption that accumulated information leads to knowledge, however, is suspect. Knowledge doesn’t “hang out there” to be picked, nor is it something that emerges from the accumulation of information. Knowledge requires context and human interpretation and understanding; knowledge changes according to circumstances and time rather than remaining permanent and definitive.

What is definitive is the human ability to learn. Knowledge is better viewed as markers along the road of learning. Our time is better labeled an Age of Learning instead of being characterized by either information or knowledge. And learning is engaging to adapt perception, knowledge (belief) or behavior to improve competence.

It is competence that truly matters. Competence starts with a body of knowledge, but quickly extends to include communication skills and the ability to work with and influence others.

Important knowledge today is rarely produced by the solitary mind; it is contextual to a given situation or area of inquiry, work or practice. For students, university “learning” is much more than the information received in class. Of comparable importance is the informal learning that occurs in discussions and activities around the campus. That is why “virtual universities” can have only a limited impact over the long haul.

Online But Off-base

A number of misleading but popular simplifications complicates the work of librarians. Perhaps the most common of these is the mantra that “everything is on the Web.”

Most university and other research libraries are stretched thin financially, so talk about “massive digitization projects” to enable all print materials to be accessed over the Internet is unrealistic. The current cost to convert books and collections is estimated at $1 per page. Budget realities eliminate the widespread digitization of library materials for the foreseeable future.

Further, while the Web is a marvelous tool for communication and the dissemination of information, it also is chaotic, ephemeral and increasingly commercialized. Web resources cited are more likely gone than active; studies suggest that the typical Web page survives between 45 and 75 days.

Keeping anything on the Web requires maintaining a server over time, which involves ongoing costs for hardware, software, data lines and staff. That’s why most Web information actually is designed to sell something, promote a particular point of view, or simply allow someone to “vent.” There’s a great deal of information out there, but the searcher increasingly finds that payment is expected for the “good stuff.” The hope of librarians and administrators that digital materials would be cheaper than print versions has been dashed decisively.

A ‘Learning Vision’

How do these insights impact the library of tomorrow? A number of questions arise: What resources do we provide, and in what format (print or digital)? What, specifically, are the goals of the library? Whom — or what — do we serve and in what priority?

If there is a dominant theme that should guide decision making, it is the issue of supporting “learning” in all its forms. Libraries are ideally suited to provide multiple support systems for people who learn in different ways. Librarians should guide learners to various resources in different media; they need to provide support for learning individually and in groups; and they must offer technological support systems and individual mentoring to help students and faculty with the variety of materials and technologies available today.

Also, the library’s perspective will have to be global. Ubiquitous automatic translators can facilitate truly global information-accessing programs.

One vision of the future is learning incubators. These would have print and digital resources on hand, with smart boards and media capabilities to allow students, faculty and professional practitioners to collaborate across time and distance in the quest for discovery and the creation of new knowledge, and where participants can analyze how they “learn best” so they can manage their own careers and personal development more effectively.

Let’s explore a day in the life of a group of FDU students in the fall of 2007. Several members of a global entrepreneurship project team meet at a learning incubator in the library. They quickly establish interactive visual links with fellow project members on the other New Jersey campus as well as at Wroxton and off-campus sites in Korea, Spain and India. The task is to develop a proposal for a global conference on small business opportunities for the preservation and recovery of usable water.

Interviews and teleconferences are scheduled with water experts at various national agencies and international organizations, as well as community development experts and community groups. Downlinks of television news programs, film clips and other graphic and audio segments allow the group to draw on vast archives of public, popular and academic programming. The students quickly assemble and edit desired information, plugging in automatic translators to make programming readily available from Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

The tools at the students’ fingertips are startling: eight-foot panels display sharp visuals and multiple-window teleconferencing; smart boards allow collaborative brainstorming and note taking, with print outs of the proceedings available at the different sites on demand. The students capture the links, images, film clips and dialogue chosen to illustrate understanding of the issues. All this can be kept as a “portfolio” of resources for reference when they tackle real-world problems after college.

But it’s not the tools available that matter most. The active and collaborative learning that takes place is the key: learning by doing has proven far more effective than passive listening or reading.

Trends or Enemies?

We live in a “visual ecology,” where we get information and communicate in a wide range of media, of which print is only one. This requires new levels and dimensions of literacy. But literacy is not enough. Further capabilities — or competencies — in finding information, accessing it, evaluating the material and using it to communicate with others and solve problems is expected as well.

The impact of the information revolution is not fully recognized. The “half life” of information usefulness has shrunk from a century or a generation to perhaps no more than days or even hours in some fields, where anything in print is automatically deemed obsolete. Today the information underlying the first year of a certain technical degree can be half useless by graduation day. Currency now prevails. Librarians must grasp the significance of this transformation. Instead of guiding learners to the authoritative book or article, it will be vital to point as well to the current “best knowledge,” and that often is the domain of a research group or even an individual wrestling with the problem in a given context.

Finally, rest assured that print resources will not disappear. They are too extensive, authoritative and well organized. Librarians love to show students how to save 20 minutes in the library with just an hour or two of searching on the Web.

The collaborative work of the hypothetical study group epitomizes and summarizes all these trends. They can draw on the authoritative print resources while delving into the new technologies. The students will walk away from this experience with a high level of “knowledge” about the issue, but even more important is the competence they will have gained by working collaboratively.

Lessons for FDU

There are things that cannot be done at FDU (or at many other academic institutions): a research library cannot be built (where the minimum threshold of resources is a few million volumes and 10 to 20 thousand journals). But, for reasons described above, neither can the library’s physical presence be dissolved in favor of a “virtual” entity.

A student survey completed last spring revealed some interesting results. Among them was the finding that satisfaction with the College at Florham Library was higher than at Weiner Library on the Metropolitan Campus, despite the fact that the latter has nearly twice the resources (books and journals) in more space, supported by more librarians and staff.

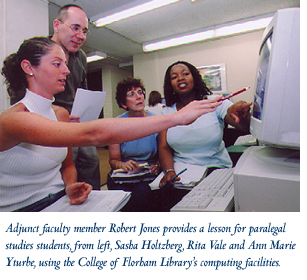

What distinguishes the College at Florham Library, though, are two items in particular: the centrality of a small accessible computer lab where students can search for information, write their papers or collaborate on their projects, and secondly the frequency of library-use instruction sessions. Many more faculty members bring their classes to the College at Florham Library for instruction in library research. Knowing how to use the technology and resources and having convenient access have a great impact on the “information literacy” skills and confidence of the students. Needless to say an intense effort is being mounted to get Metropolitan Campus faculty to bring their students to the library more often.

FDU’s library needs are being addressed by approaches that might be labeled either technological or partnering. The technological includes a new, dynamic Web page (http://alpha.fdu.edu/library), and — in January — a new Web-based library system (Voyager). “Partnering” includes initiating programs of outreach, collaboration and innovation. Library friends groups are being revitalized; book reviews and discussions and movie showings are planned; extensive efforts are under way to insert “information literacy” efforts into the curriculum; library advancement initiatives are under discussion to make the library a center of intellectual life on both University campuses; and strategizing has begun on how to mount a serious renovation-construction initiative for the College at Florham Library. Attention is being given as well to providing better support to off-campus learning sites.

Bringing visions to life is never an easy task, and libraries certainly have much adapting to do in order to seize the promise of new technology. While many events cannot be predicted, one thing is certain: libraries will continue to play a strong role in the learning process. Perhaps the most absolute statement that can be made is that the library of the future will be both very similar to and yet very different from the library of today.

For information on the resources available at FDU’s libraries, call the College at Florham Library at 973-443-8532 or Weiner Library at 201-692-2278. Alumni are automatically entitled to a library card for life and can obtain one by calling the Office of Alumni Relations at 201-692-7013.

FDU Magazine Home | Table of Contents | FDU Home | Alumni Home | Comments