|

FDU’s Adele Stern: Remembering a World at War

By Art Petrosemolo

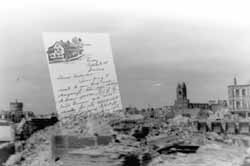

The letters in Adele Stern’s scrapbook are fading, the stationery — more than a half-century old — is fragile. The black-and-white photos brought a smile to Stern’s face as she recalled memories of some 55 years ago. “It was a different age,” Stern says softly, “a different time. The world was at war, and everyone had a friend or relative overseas. We all wanted to help in any way we could.” For Stern, helping meant nearly three years as a Red Cross volunteer in war-torn Europe, much of the time with the Army of Occupation in Germany. Not many people at FDU know of Stern’s World War II service. I was pointed in her direction by a colleague after reading Rosemary Norwalk’s 1999 book Dearest Ones, which chronicles, through her letters home, two years as a Red Cross volunteer, much of it spent as a “doughnut girl” in England and Germany. “You know, I think Adele Stern had a similar experience,” my colleague said. When I called Stern and asked if she would be interviewed for a story and would share her photos, she asked, “Who would want to do a story about me?” Well I would, I answered. I was born midway through the war, and I have always had a fascination with how this country and the world mobilized in the 1940s to fight Adolf Hitler and how the war touched so many lives. I thought, as we approached the new millennium, it would be story that would interest many and give us all a chance to “remember when.” So, for a short time in early summer, Stern relived some of her wartime experiences as a Red Cross volunteer. Stern, then Adele Hyrkin, a young Jewish girl from Brooklyn, volunteered for what turned out to be an adventure of a lifetime thousands of miles from home. After graduating from college in 1940, she was having difficulty getting her teaching career in high gear in New York City. In the early 1940s, she visited friends who were teaching at a private school in Miami, Fla. She liked what she saw and she soon joined the staff at The Lear School. Within two years she had become the school’s assistant director.

“But with the war under way, everyone wanted to help,” Stern says. “Much to my parents’ chagrin, I volunteered as an American Red Cross (ARC) worker in late 1944; trained in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Md.; and was shipped to Europe on a troop convoy departing from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, not far from my home. “Many of the volunteers had never been on a ship before and many people got seasick,” Stern recalls. “There was great concern about German U-boat attacks,” she continues, “as Hitler had put rockets on his submarines, and no one was sure how accurate they were.” Stern remembers being evacuated to lifeboats in the middle of the Atlantic when submarines were in the area. “When we reboarded, we were told to stay away from the portholes,” she says. But curiosity got the better of her, and she did look and saw her ship actually ram the submarine. “I got seasick immediately,” she remembers, “not from the waves but from thinking of the kids in that submarine, no older than I, who were heading for the bottom of the Atlantic.” Stern arrived in Paris just after the liberation of France. “Paris was the jumping off point for ARC volunteers,” she says. “My first assignment was in Belgium, where I drove a doughnut truck.” Doughnut trucks were self-contained vehicles manned by Red Cross volunteers who provided doughnuts, coffee and refreshments for troops at embarkation points or, at times, very close to the front lines.

On one assignment, Stern got so close to the front lines she'd prefer to forget it. “I was driving a truck in Belgium,” Stern recalls with a smile, “delivering coffee and doughnuts to troops. Suddenly the GIs, afraid for our safety, started screaming at us and found a way to point us to Allied lines. We had been in the middle of the Battle of the Bulge at Bastogne, Hitler’s last major counteroffensive of the war.” Fortunately, Stern and her Red Cross partners emerged from the forest unscathed. Her next ARC assignment was in Fritzlar, a small town in northern Germany, which was then under Allied control. Stern was flown into Germany and literally dropped off in the middle of an abandoned airfield with her bags ... to wait for her GI pick-up. She ran a Red Cross club in Germany for several months before returning to Paris, spending V-E (Victory in Europe) Day in Paris. “At the Ritz Hotel, I actually ran into Ernest Hemingway and got a big V-E Day kiss,” she remembers. Unlike many ARC volunteers, who came home after the end of hostilities, Stern re-entered Germany with the Army of Occupation and was stationed in Bavaria in a small market town called Straubing, where she served the remainder of her time. Stern’s experiences in occupied Germany after the Nazi surrender are memorable, and today she speaks of details as if it all happened yesterday. Driving around Bavaria in a Red Cross vehicle, Stern found 13 Hungarian women who had just been liberated from Auschwitz. “When they saw me in uniform, in a truck, they were frightened,” Stern relates. “They were lost, hungry, had been separated from their families and were literally without much hope.” Stern took the group back to the Air Force base and gave the women jobs. Many of them stayed nearly two years, regaining their health and their hope while helping Stern run the Red Cross club.

Stern said one woman, Ada, wanted to return to her homeland to find her husband and children. “I advised her against it,” she says, “as Czechoslovakia was then under Russian control, and she had no money, no ride. “But the woman insisted on trying,” Stern continues, “and six months later she returned to Straubing with her husband and children. We were amazed.” Stern was at the evacuation of the Dachau concentration camp in 1945. “I saw living skeletons walking haltingly out of the camp,”Stern says, “and bodies being carried out and stacked like cord wood. The odor was fierce,” she continues, “I’ll never forget it or get over it.” Stern also remembers more pleasant experiences. She smiles when recalling one event. “I was driving the truck in Bavaria when I saw a castle in the distance. I drove up and found GIs occupying the site. They called me ‘Yankee Girl.’” When she toured the castle, Stern found rolls and rolls of expensive damask silk fabric that had been stolen from France by the Nazis and hidden away. The soldiers cut five rolls into bundles and she sent them home. She says that family and friends used the fabric for years for upholstery, coats and drapes. “And to this day, I still have five yards as good as it was 55 years ago.” Stern also had the opportunity to see the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials. “I was wearing a uniform so they let me in,” she says, “and I had a chance to see Goering and other high-level Nazi officials for several days.” Stern wrote to her family throughout her Red Cross overseas posting, and her letters begin “ Dearest Mother Dear,” which is very similar to Rosemary Norwalk, who started her family letters “Dearest Ones.” Both mothers kept the letters in scrapbooks for their daughters to treasure over the years. Earlier this spring, Stern returned to Germany for the first time in 55 years. “I wasn’t comfortable,” she says, “the language triggered feelings I had not had for decades. My companions visited the concentration camp sites, but I would not go. My experiences in the Second World War suddenly were reawakened — war-time memories all too real — and they gave me pause.” In recognition of her work and to honor her as a spokesperson for women’s rights, Teaneck-Hackensack Campus Provost Paula Hooper Mayhew this year asked Stern to give the keynote address at the dedication of the Susan B. Anthony Conference Room in Robison Hall on the Teaneck-Hackensack Campus. Stern said in her presentation, “I came home [from the war] a different person from the wide-eyed girl who had gone to help our boys save the world for democracy and to a different America.” Adele Stern has played an influential role in that new America, helping to school future generations while sharing first-hand memories of perhaps the most important collective effort of the century. |

||

|

Stern's Pictures | Top of Page FDU Magazine Directory | Table of Contents | FDU Home Page | Alumni Home Page | Comments |

|||