Summer 1999

FDU Magazine

|

FDU ·

publications ·

FDU

Magazine · calendar of

events · help

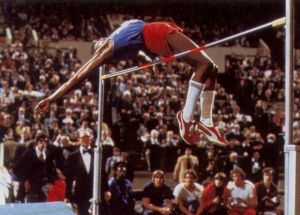

Franklin Jacobs Reached New HeightsWorld-class High Jumper Rose Above All, but Politics Denied Him Olympic DreamBy Arthur Petrosemolo TWENTY YEARS AGO FDU's Franklin Jacobs was a rising star in track and field. He set a world high-jump record at the prestigious Millrose Games in 1978, was undefeated and ranked number one in the world during the 1979 indoor season and was a favorite for a medal at the 1980 Olympics. But as quickly as Jacobs appeared on the scene, he disappeared; his dreams dashed with the U.S. Olympic boycott. Now, two decades after his short, sensational career, still holding the Millrose record and a Guiness Book of World Records' mark for clearing a bar 23.25 inches over his head, Franklin Jacobs' name is known only to dedicated track fans or as an answer to a sports trivia question. Ironically, Jacobs stood only 5 feet 8 inches and didn't start to high jump until 1976 when, as a senior at Paterson (N.J.) Eastside High School, he cleared 6-8, winning the state scholastic championship. Less than two years later, as an FDU sophomore, he set the world indoor record. Although he had been consistently jumping over seven feet in 1978, the Millrose victory was Jacobs' first win of the season. In the process, he beat the gold and silver medalists from the 1976 Montreal Olympics along with U.S. high-jumping legend Dwight Stones. Jacobs was a hot story; columns and features on him appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek and Sports Illustrated, and stories were broadcast on national network television news programs. But he saw his accomplishments merely as interim steps on the way to an Olympic medal and clearing the magic 8-foot mark. Jacobs' world indoor and outdoor records have been eclipsed by a new generation of athletes. The current world indoor record is 7-9 1/4 and the outdoor mark is 7-11 1/4. Still, 21 years later, his Millrose record stands and is remembered as one of the most exciting moments of track and field. Jacobs, though, has settled far from the scene of his former glory. In 1998, on the 30th anniversary of the new Madison Square Garden, the Millrose Games honored its top performers. Jacobs was selected, but it took nearly three months for meet director Howard Schmertz to locate the athlete, who now lives in Arizona. "I was thrilled to come back to Madison Square Garden to be honored with other Millrose champions," Jacobs says. "I had not thought about that time in a while, and it was nice to know that other people remembered." [FDU also well remembers his feats, and this year Jacobs was named a charter member of the Division I Hall of Fame.] Making His MarkWell into the competition on that wintery 1978 January night in New York City, the Millrose high jump had become a two-man duel between FDU's Jacobs and the defending champion and Olympian Stones. The event turned strategic as Stones, known for his gamesmanship, suggested to Jacobs they put the bar at world-record level. Many still believe that Stones, ahead on fewer misses in the competition, had figured both would not clear the record height so early in the season and he would win the competition on fewer misses. His plan backfired.Both jumpers unseated the bar on their first two attempts to clear 7-8 1/4, but Jacobs had the height. His jump coach, Bill Monahan, suggested Jacobs move his approach back to 14 steps for additional speed in the run-up. It worked; and although Jacobs brushed the bar going over -- "it seemed to quiver for 30 seconds," reported The New York Times -- it didn't fall. Jacobs had set a new world record and the crowd of 19,000 erupted with delight. The New York Times described Stones' last jump to keep the competition alive as "esthetic but unsuccessful." Unlimited PotentialJacobs' performance at the Millrose Games was one of many highlights in his career. He came to FDU in the fall of 1976, after starring on a high school basketball team that had been rated first in the state. Jacobs was a sparkplug of the Eastside squad and was known for his ability to slam dunk. "I actually could get my head to touch the rim," he recalls, "which when I think about it is pretty amazing and probably pretty dangerous."At Eastside, Jacobs joined the track team after basketball, and he recalls clearing 6-1 in his first day of practice without any real technique. He won the state championship a few weeks later. Jacobs followed his older brother Elijah Scott, BA'75 (T-H), now working for IBM in North Carolina, to FDU. He was welcomed to the Teaneck-Hackensack Campus by then-trustee Elia Stratis, BS'67 (R), MBA'76 (T-H), who was instrumental in helping attract many athletes to the University. Jacobs recalls Stratis, who was tragically killed in the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 in 1988, as "a good friend and role model." FDU Track Coach Walt Marusyn knew Jacobs had unlimited high-jump potential if he refined his jumping technique and concentrated on the sport. At FDU, Jacobs' vertical leap was measured at an incredible 44 inches. "I sat down with Franklin and told him that he was a 7-foot high jumper in the making and his eyes lit up," Marusyn says, "and after one season of FDU basketball, he focused on the high jump." Marusyn knew Jacobs needed additional help if he was going to compete in this elite class. Marusyn sought the help of Monahan, who had strong field-event coaching experience. Monahan taught Jacobs a 13-step curving approach to the bar, which got him off the ground quickly. "Franklin then exploded over the bar," Monahan recalls. "It wasn't pretty, but it worked." In the 1970s, track athletes competed year round. An organized indoor circuit and invitation season filled the winters between traditional outdoor meets and Olympic competitions. Jay Horowitz, FDU's sports information director in the 1970s, who went on to become media director of the New York Mets, served as Jacob's mentor and traveling companion through the winter seasons. Horowitz remembers Jacobs as someone special. "He was very competitive," Horowitz says, "especially at big meets. He literally put FDU in the national spotlight." A special bond developed between the pair. Horowitz says his press credentials allowed him, unlike the coaches, to get into the infield at indoor meets. "Franklin would ask me to watch where he planted his takeoff foot," Horowitz says, "And I could advise him if he was on or off the mark." Jacobs says Horowitz helped him tremendously, mentally and physically. "He was very, very important to me at the time." Russ Rogers, FDU's track coach from 1978 to 1988, who now coaches at Ohio State, recalls that in 1979 Jacobs had a 13- meet undefeated streak. "At times," Rogers says, "Franklin didn't even start to jump until the bar reached 7-2, and I remember him winning one competition where he didn't even remove his warm-up pants." Rogers' fondest Jacobs memory was of an indoor championship in Long Beach, Calif., in 1979, when Jacobs again went head-to-head again with rival Dwight Stones. Stones graduated from Long Beach State, and he had the high-jump pit surrounded by a group of loud friends. Stones missed at 7-6 and then asked to move the bar to 7-7 with one attempt left. Jacobs cleared 7-7 on his first try, and when Stones missed the audience couldn't believe it. Rogers says, "You could have heard a pin drop. He beat the Olympian again but this time in his own backyard." A Dream DeniedFranklin Jacobs successes were tempered with a growing concern that the United States might boycott the 1980 Moscow Summer Games. "I just couldn't believe we wouldn't go," Jacobs says, "it was the Olympics. I was sure a compromise would be reached."Track stars who went on to Olympic glory often were able to cash in on their victories with endorsements, television commentator positions or book contracts. Jacobs felt he was destined for similar fame. President Jimmy Carter, however, pulled the U.S. team from the games to protest the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan. "Franklin was so focused on the Olympics for two years," Horowitz recalls. "It was his goal and what he believed would be a ticket to a better future for him and his family. When President Carter said we wouldn't go, Franklin wasn't sure he could maintain his peak form for an additional four years, and I think he lost all his drive. The United States did hold Olympic Trials in 1980 at Eugene, Ore., and today Jacobs has different thoughts about the time leading up to the trials and the events in Eugene. "I was still young and impressionable," he remembers, "and had been approached by a number of athletes about ways to make a protest statement about our Olympic boycott. I decided to let the bar get to 7-3 inches at the trials before I started jumping, which was unheard of. I planned to clear the height and stop. It would be my protest. Unfortunately, I missed my three attempts, and it was over. "At the time, I was rated number one in the world," Jacobs says, "and rethinking it today there are other things I could have done which would have been just as effective." Jacobs did not return to FDU in the fall of 1980 and disappeared from track and field for four years. He worked in Paterson, N.J., and was serving as a youth director at the YMCA when a co- worker encouraged him to give it one more try in 1984. Jacobs contacted Monahan and after less than a month of training, entered the Mobil Oil Indoor Games at the Meadowlands Arena, one of the indoor meets leading up to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. To everyone's surprise, Jacobs won thehigh jump at 7-4 1/2, qualifying him for the Olympic trials. With nagging knee problems, however, and lack of training, he was unable to compete at the trials, and his high-jump career ended. Jacobs turned away from the spotlight to focus on his family. He married Naomi Livingston, BS'88 (T-H), and they had a daughter, Shannon (now 7). "I worked at the time to support my family," Jacobs says, "but when Naomi got a chance for a job relocation to Phoenix, we decided it was time to make a new start." Jacobs' move to the Southwest has been good for him and his family. He works as a superintendent for a residential builder. "I'm content with my life. I'm very happy," he says. "No one here in Phoenix knows of my exploits. I work out in a fitness center all the time and do a lot more weight training now. My high-jump career was another life, and I haven't shared it with friends and neighbors here in Arizona yet." A little older, a little wiser and happy with his life in Arizona, Franklin

Jacobs has reached a sense of balance in his life. "You can't change the

past," he says, "and although I might have done some things differently,

it was a great time. And a time I'll always be proud of."

|

| Copyright © 1999, Fairleigh Dickinson University. Information on the FDU web pages is provided as a convenience for the University community and others seeking information. While the University intends the information distributed here to be accurate and timely, it is the responsibility of the user to verify the information. | |