Into the Deep

Mensun Bound, director of exploration of the Endurance22 expedition, on the sea ice of the Weddell Sea in Antarctica. (Photo: Esther Horvath and Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust)

Mensun (Michael) Bound, BA’76 (Ruth)

By Kenna Caprio

Mensun (Michael) Bound, BA’76 (Ruth), answered interview questions for this story between flights to Buenos Aires and to Ushuaia, Argentina, and then from a boat headed to Antarctica.

A born explorer, he’s always a man on a mission or a new expedition.

Growing up in the Falkland Islands, Bound often heard stories about Ernest Shackleton, the famed Antarctic explorer. When he received a book about Shackleton, Bound read it cover to cover, learning about Shackleton’s doomed ship the Endurance and his harrowing, icy survival with his crew in 1915. As a teenager, Bound even drove Shackleton’s son Edward around the islands on official government business.

Though the lore of Shackleton and the famed shipwreck surrounded him, it wasn’t until Bound arrived at FDU that he considered a career in maritime archaeology and exploration.

“Long story, but FDU took me at the last minute, and then I found myself studying under an inspirational group of teachers who fired my interest in archaeology and the ancient world,” says Bound. “It was one of the most stimulating and rewarding times of my life. The Rutherford Campus came the closest I’ve ever known to the academic ideal — a community of teachers, scholars and students, all sharing a love of knowledge for its own sake.”

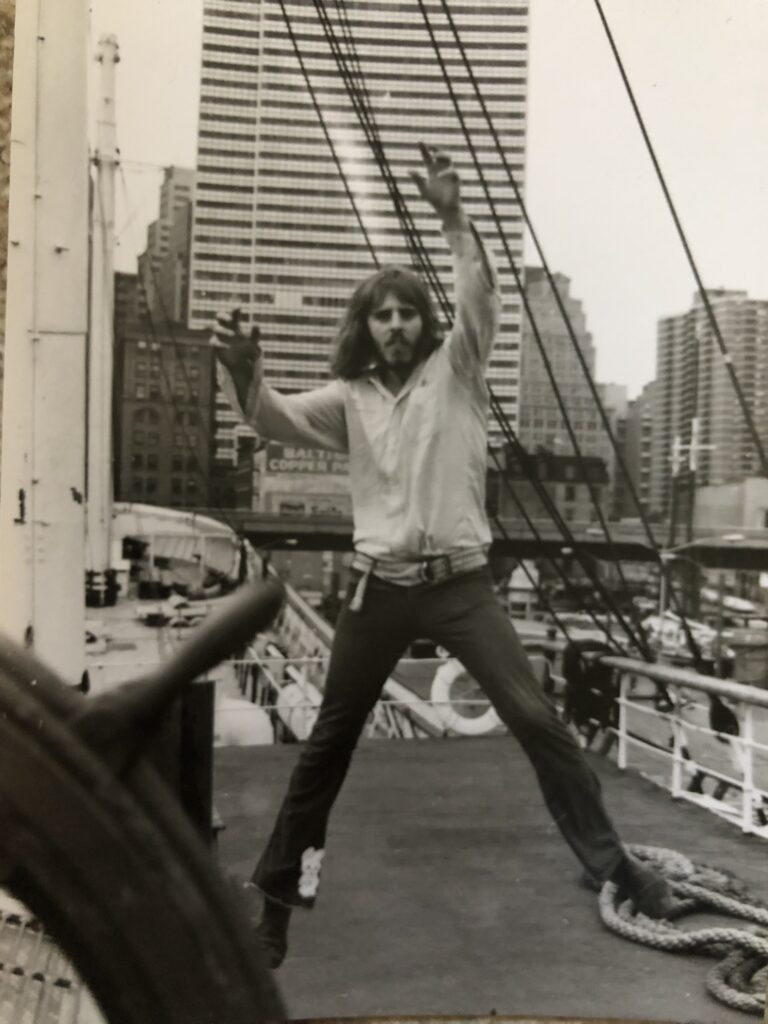

Bound as a student at FDU, volunteering at the South Street Seaport Museum in Manhattan. (Photo: Courtesy of Mensun Bound and Joanna Yellowlees)

The late John Dollar, professor emeritus of humanities; the late Anthony Alessandrini, professor of social sciences; the late Charles Angoff, professor of English; the late Robert Laurer, professor of art; and Samuel Raphalides, professor of political science and history and director of the Global Scholars Program on the Metropolitan Campus, all had a profound impact on Bound.

“FDU was pivotal in my life. Everything I have achieved can be traced back in a straight line to FDU,” he says.

Through FDU connections, Bound found work as a research assistant at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, N.Y., with a focus on ancient Greek vase painting. “Before I knew it, I was spending my summers on a Roman villa excavation in Italy.”

He directed his first underwater excavation as a graduate student at the University of Oxford, England. The ship, down 50 meters off of the Italian Island of Giglio, was an Etruscan wreck circa 600 B.C., carrying Greek painted pottery, olives, olive oil, pitch, musical pipes, writing tablets, carpenters’ tools, amber and more. Recovered items and materials from the Giglio wreck are on permanent exhibition at the Spanish Fortress in Porto Santo Stefano, Italy.

“In the late 1990s, I directed the deepest hands-on excavation ever. The Hội An wreck went down in the South China Sea, off the coast of Vietnam,” says Bound. “This was also the biggest, most expensive and, arguably, the most dangerous excavation. Because of the depth, at 70–80 meters, the only way to excavate the wreck was to use saturation-diving methods. Divers had to live in chambers on deck, which were pressurized to the depth of the seabed. They were carried to and from the wreck in a dive bell that docked with the living chambers.”

Bound directs the excavation of the Dutch East Indiaman ‘Nassau’ for the National Museum of Malaysia in 1995. (Photo: Courtesy of Mensun Bound and Joanna Yellowlees)

Excavation and marine archaeology can be a dangerous profession. “Whenever we had divers down, I’d get tied up in knots with worry until they were all back and safe,” he says. Over the years, Bound has had a few close calls, suffering a bout of hypothermia on the Hội An wreck and nearly running out of air once on the Giglio wreck. “These days, all my work is robotic, and I love that because there’s no risk to life. I can just relax and enjoy it all.”

The Hội An wreck was worth the risk, Bound says, because the cargo — “beautifully painted ceramics and figurines — is from Vietnam’s second golden age of the 15th century, and little else from then has survived.” The recovered artifacts now reside in six museums across Vietnam.

“I love the discovery of new knowledge that comes with archaeology, and I’m fascinated by the underwater world,” he says.

Ultimately, Bound’s commitment to making new discoveries led him back to Shackleton and the Endurance.

“Finding the Endurance was 10 years in the making,” says Bound. He and a friend first discussed the possibility back in 2012. It took time to convene an expert team; assemble a fleet of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs); secure funding; find a suitable ice breaker; conduct research; and draw up a search area. The team made a first attempt in 2019 — “it ended in disaster” — with their AUV simply vanishing.

Mensun Bound takes an angle on the sun with a sextant that’s identical to the one Endurance Captain Frank Worsley used in 1914-1916. (Photo: Pierre Le Gall)

They recalibrated and “went back with a new vehicle tethered to the ship by a Kevlar-sheathed fiber optic cable and run by a subsea team with underwater engineers.” As director of exploration for the Endurance22 expedition, Bound determined the search area parameters.

On March 5, 2022, the team found the Endurance in the Weddell Sea of northwestern Antarctica. “She was upright and in a brilliant state of preservation.

”Following the discovery, Bound said, “This is by far the finest wooden shipwreck I have ever seen. You can even see ‘Endurance’ across the stern. This is a milestone in polar history. We are bringing the story of Shackleton and the Endurance to new audiences and to the next generation.”

Endurance found. (Photo: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust/National Geographic)

Bound wrote a book about the experience — The Ship Beneath the Ice — which grew out of his expedition blogs, diaries and daily reports. A documentary about the Endurance discovery is forthcoming from National Geographic. In late February and early March 2024, Bound will be a guest speaker on board a voyage to South Georgia Island and the Falkland Islands.

His is a heart and a mind always at sea.

GREAT READ

“The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini is one of the greatest written works of the Renaissance. It’s unfinished. The last line, ‘And then I left for Pisa,’ just kind of fell off the page. Brilliant.”

ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCATE

“I’m a passionate environmentalist. It’s hard not to be when you’ve spent as much time as I have in and around the Great White Continent. It’s a continent in pain, and what happens there matters because what happens in Antarctica happens in the rest of the world next.”

DEEP DIVE

Bound completed “rigid-helmet mixed-gas training” to become a professional diver. “This enabled me to dive much deeper and stay down for longer.