Aeolian Organ

When the University opened its Florham campus in 1958, the Aeolian organ was still in place outside the drawing room — currently known as Lenfell Hall — the pipes extended into the second floor lounge outside the former master bedroom suite. The organ was installed in 1918, eight years after the death of Mr. Twombly, at a cost of $85,000 for the organ and installation, and had more wiring than the one in Radio City Music Hall.

Mrs. Twombly entertained company every weekend during Spring and Autumn, sometimes for simple events, ranging from 12 to 30 guests. Larger events and dinners included as many as one hundred and fifty guests. For these special occasions, Archer Gibson — the “Millionaire’s Maestro” — came out from New York to play the organ during dinner. He was paid $750 for the evening. He was the consummate advocate of the Aeolian residence organ.

Mrs. Twombly entertained company every weekend during Spring and Autumn, sometimes for simple events, ranging from 12 to 30 guests. Larger events and dinners included as many as one hundred and fifty guests. For these special occasions, Archer Gibson — the “Millionaire’s Maestro” — came out from New York to play the organ during dinner. He was paid $750 for the evening. He was the consummate advocate of the Aeolian residence organ.

While the organ played, Mrs. Twombly sat to its left on a throne. When she signaled, the organist would play his last piece, and she would rise and ascend the marble staircase to her bedroom, signaling the end of the party.

After the university purchased the Mansion, students resided on the third floor, and they fondly remember the sounds of the organ. Former student, Patricia Moran, BS ’63 recalls:

“There was a student who used to come in on Sunday mornings and play it. When you came down in the morning (from the third floor dormitories) the whole Mansion was filled with the music”

Alas, change arrived. The University needed to comply with construction and fire codes. Dean Griffo explained the changes in a letter to the students in September 1967:

“The estimate of $21,000 necessary to put the organ in good working condition is only part of the story.

“Over the past two years the University has complied with fire regulations by removing a number of serious electrical violations in the Mansion. One renovation involved re-wiring and the conversion of our single-phase circuit to a three-phase electrical circuit. The organ motors and all electrical parts were manufactured to function under the old single-phase circuit. In order to activate the organ, it would have been necessary to purchase all new motors and electrical parts capable of handling three-phase circuitry. The estimated cost of this change was somewhere between $25,000 and $35,000. After three-phase wiring was completed the organ was non-functional.

The students in 1967 were angry. An editorial in the student newspaper asked:

“Was it worth the price of peanuts to give away an important part of our campus’ culture – a vital link with the past?

“No, we say. We feel that by selling the Twombly organ, the school is missing the point, the essential point. That is, that we are and have been sorely neglecting the cultural, the aesthetic side of education. Thy physical is dominating the artistic, the more fragile. An important balance has been tipped here.”

Dean Billmeyer, a professor of Organ and Harpsichord at the University of Minnesota School of Music, recalls coming to Florham as a 12-year-old boy to dismantle the organ with his father and take it away to their home in New York State.

“… concerning the Aeolian organ, Op. 1428, formerly owned by the Twombly family, I was only 12 years old when Dad bought this organ in 1967, but I recall he bid for it after seeing it advertised in The Diapason, a national monthly publication. Dad’s was the only bid received! Dad and I, with some assistance from my siblings, as well as Dad’s students at Rensselaer Polytechnic University, installed the organ in our home in Niskayuna, NY. We had another, smaller pipe organ in the home, which Dad subsequently donated to St. George’s Episcopal Church in Schenectady.

“Residence organs of the early 20th century were the possessions for the very rich. These organs were largely fading as sources of entertainment by the 1920s, being replaced by the phonograph and radio, and the Aeolian Company merged with the E. M. Skinner organ company in 1930. By then, manufacture of residence organs of this type had effectively ceased.

”Of the Twombly organ, we were able to get it playing in part. The antiphonal division (15 ranks, or about 20% of the entire organ) was quite intact, with its own wind supply; and its chests and action did not suffer the degree of deterioration of the rest of the organ. The console was not in good condition, and so Dad purchased another console, used, from the Skinner organ at Royce Hall, UCLA (a very famous organ, still intact). The UCLA console was later sold to the Reuter organ co. (Kansas), and I have heard anecdotally that it serves a church in the Chicago area. We used the UCLA console to play the Aeolian from about 1969 onward.

”When my parents needed to sell their home in the 1980s, Dad and I looked very hard for several years for a home for the Aeolian. Such instruments are most difficult to relocate: the style of this organ made it difficult to serve a church, and the cost of a complete restoration would have been tantamount to the cost of a new pipe organ. Ultimately, Dad was able to donate the Antiphonal organ to Boston University, where it was to have served now as part of BU’s Symphonic Organ. It is not apparent, however, that it remained in this instrument.

“Ultimately, pipe work and other parts from the Aeolian were given to local organ builders in the Schenectady area. It is sad to have to inform you that the Aeolian no longer exists in its entirety. However, its presence in our home was of immense educational value to us, and it is my belief that the organ is still preserved in part in Boston.”

Nelson Barden,Boston University’s organ curator, provides the wrap-up:

Each Aeolian organ was identified by an Opus Number, and the Twombly organ was Opus 1428. The story of Florence Vanderbilt and Florham, as well as the pipe specification and a photo of the console may be found on pages. 85 – 90 of Rollin Smith’s book “The Aeolian Pipe Organ and Its Music.” The contract was signed on November 21, 1918 for $65,937, and the organ was shipped from the factory on June 28, 1919. Further information is in “The Vanderbilts in my Life” by Shirley Burden, Mrs. Twombly’s grandson.

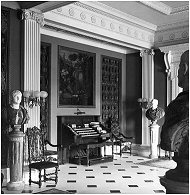

As residence organs go, the Florham Aeolian was a very large instrument. The console had four keyboards and a total of 71 sets of pipes, called “ranks.” The console was installed at the end of the entrance hall which was hung with Florence’s famed Barberini tapestries and extended 150′ across the front of the house. The main section of the organ was in a chamber stretching from the sub-cellar to the first floor ceiling. The Echo/Antiphonal Division had 16 ranks of pipes and was installed in a second-floor room at the top of the grand staircase.

We removed the Echo / Antiphonal from the Billmeyer house about 1986. It was completely rebuilt in the restoration studio of Nelson Barden Associates at Boston University and enlarged to 28 ranks. Renamed the String Division, it was incorporated in the John R. Silber Symphonic Organ, where it remains today, see http://www.nbarden.com/buso/welcome.html

Times change. The Aeolian 1428 is gone. The Aeolian Company declared bankruptcy in 1985. Only Archer Gibson, the organist, lives on in the CD world.

Submitted by Linda Carrington